How do I know when I’ve spent too much time in Excel?

When I see this:

That’s a Classic Essbase Excel add-in message and proof that I was doing waaaaay too much analysis of a particularly knotty data issue. In almost 20 years of Essbase work (most of it with the add-in) I have never managed to get that error message. I took it as a note that it was time for me to stop and take a coffee break.

But that’s not what this blog post is about. What this blog post is about Yet Another Stupid Excel Trick because of Yet Another Manual Process.

I must give mention of Mabel Van Stone who tried to warn me of this issue. As usual, I heard it, but didn’t hear it. Now I am going to write it. Maybe this time it will actually sink in.

The hell that is linked workbooks

If you read my last blog post on this subject, you’ll know that I am not exactly a terrific fan of linked Excel workbooks because of the potential of completely mucking up the data.

I also am not exactly a terrific fan of: mean people, stupid people (although on reading this post you may be convinced that I am part of that group), injustice, bad coffee, and a whole host of other things. Me not liking them matters not a jot as they exist with or without my approval. What does matter is knowing what defines “bad” and then firmly following one of two paths: avoidance of things I cannot change (and grudging acceptance therof) and the complete eradication and expiration of the things I can change. Sometimes run and hide is the answer, other times violence is the answer. Yes, I am a simple man. What I am about to illustrate falls into the former category.

Source and linked target open at the same time

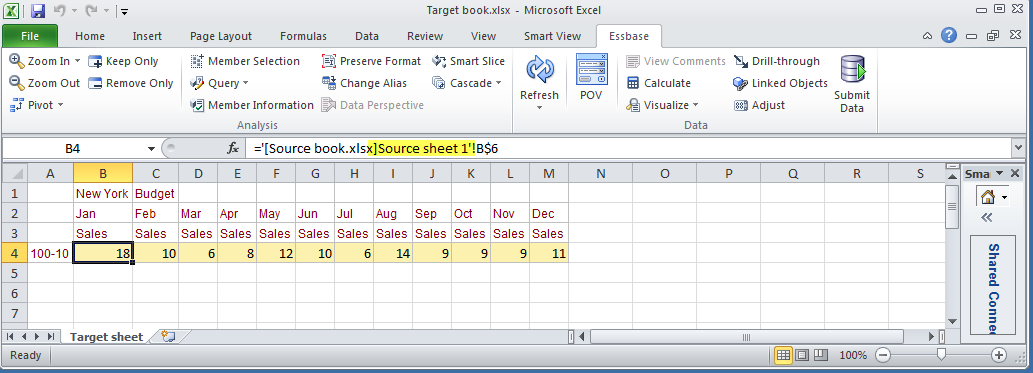

Let’s begin with a simple (hah!) example of linked workbooks, this time with both workbooks open.

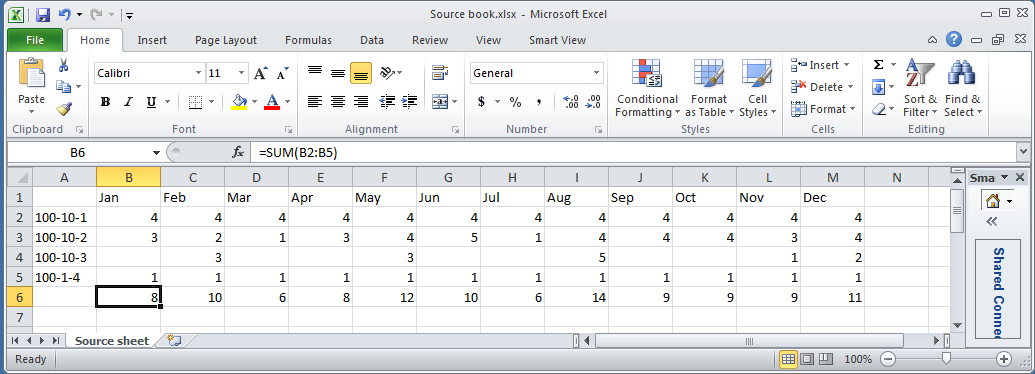

Source

Do the products in column A look familiar? No? They are Cameron’s detail skus to MVFEDITWW (pronounced mmmfeditwwwuuua) aka Sample.Basic.

Target

And here is that linked target in MVEDITWW’s send workbook:

Note that the total Excel formula value in the send sheet’s row 6 is linked to the target sheet’s row 4.

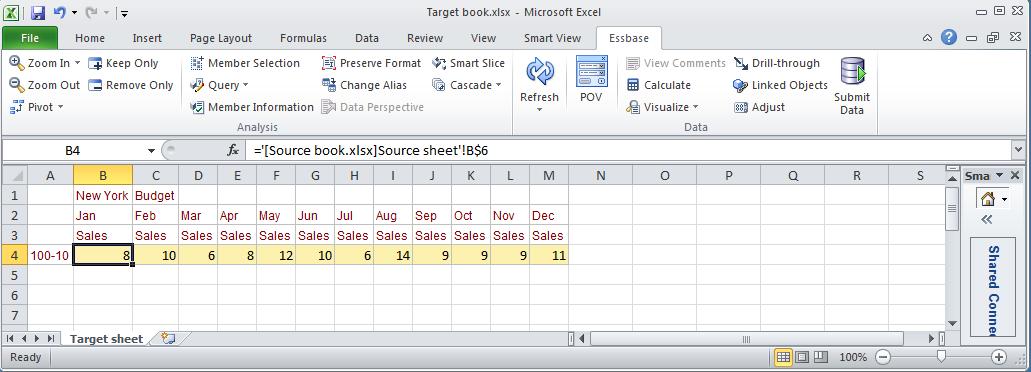

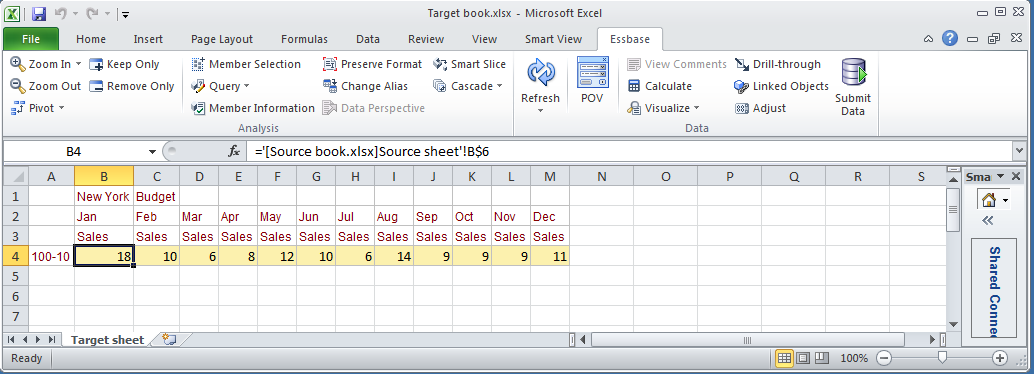

Updates

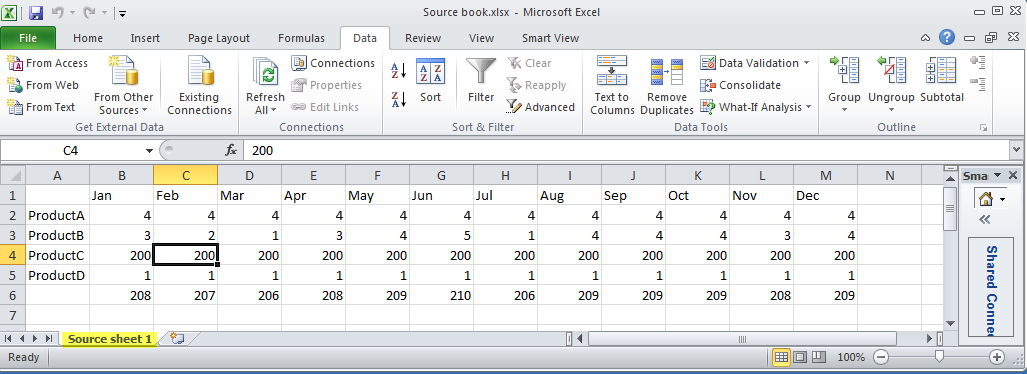

A change in the source:

Is reflected in the target immediately as both workbooks are in memory:

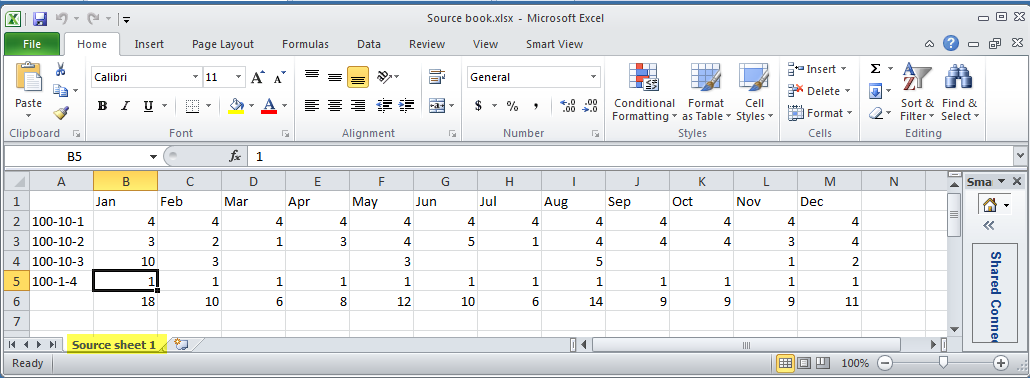

Sheet renames

If the source sheet is renamed from “Source sheet” to “Source sheet 1”:

It is reflected immediately in the target workbook formula:

All very slick and goof proof. Maybe.

Closing the files

That’s great if you have both workbooks open, but it’s often common practice, aka some form of sanity to keep just one workbook open at a single time so what’s being dealt with is obvious.

To keep an even greater degree of sanity, it is also common to disable the automatic updates of linked workbooks. Maybe you want the target workbook to be updated, maybe you don’t. The only way to control this is to:

- Go to the Data ribbon

- Click on Edit Links

- Click on Startup Prompt

- Click on Don’t dipslay the alert and don’t update automatic links

This then puts you in control of updating or not.

I like this because I in general like control of my data and also because it makes this example easier to demonstrate. NB – the functionality is the same if automatically updated so that is not a free ride to getting away from the Excel Stupid Trick.

Closed source workbook

So what happens when data gets changed in the source and then saved and closed?

It’s not updated until it is explicitly updated by you, oh Excel god.

Updating is easy, simply go to Data->Edit Links->Update Values and the new numbers are reflected in the workbook. Simple and again you are in control.

Renames

What happens if you rename the old sheet and then save and close?

On update, Excel knows that the sheet formerly named “Source sheet” is now called “Source sheet 1”. It is not tied to the number of worksheets in case you were thinking it went off of the index of sheets in a book. Somewhere in the depths of Excel, there’s a code associated with the sheet name. We see it as “Source sheet 1” or whatever; Excel has its own name that allows this kind of renaming whilst retaining the links.

Note that before the update, the sheet name is the old “Source sheet”. After the update it is “Source sheet 1”.

This is all pretty awesome, isn’t it? What oh what oh what could possibly go wrong?

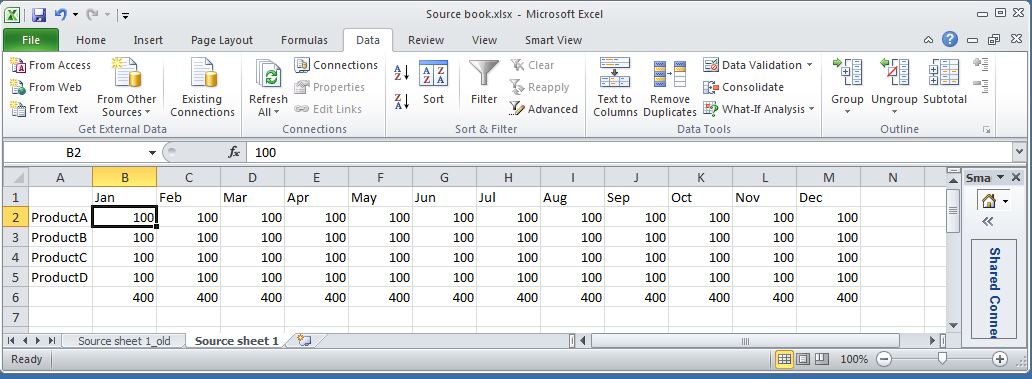

New sheet with the same name

If I create a backup of the old sheet (hey, I may want to go back to the old data) and create a new sheet with new data, what happens?

In the example above, Excel used (I think) some sort of internal sheet code to keep the link to the renamed sheet, ignoring the displayed sheet name of “Source sheet 1”.

I’ve renamed the original sheet with an “_old” suffix and created a new sheet with the same layout but with a the original sheet name.

Excel is smart enough to see this and gives you a choice of sheets – original one with the “_old” suffix or the new sheet with the original “Source sheet 1” name. Saved from certain disaster I bow down again before the genius of Microsoft. Or should I?

A modest man with much to be modest about

We have now reached the inspiration for the title of this blog, and alas and alack, there is no false modesty here. What do I mean by this? I simply mean that as you can see from the above, Microsoft made linked workbooks, at least from the source sheet perspective, goof proof. Believe me, I tried very, very, very hard to break Excel in the course of building the samples for this blog post and I just could not make it happen.

And yet I managed to make a mess of linked workbooks even after being warned that just such an error could occur. How did I manage to do this? Read on so my humiliation can be complete.

Screwing up, step by step

1 – Prerequisites

Environment

I have thus far shown you a very simple set of workbooks and sheets.

Imagine a very complicated set of linked workbooks, with the source being the user set of workbooks that define base budget information and the target being a series of linked worksheets that send data to Essbase. When I say complex, I mean there might be 20 to 70 (yes, you read that correctly) sheets in the source workbook and at least that many in the target. Within each sheet is a link range (think of it as a mapping of source layout to target layout) and then there is another range of linked (this time only within the sheet) formula cells that are selected and sent to Essbase. And before you start tsk-tsking, remember that this is not my process – I am just a caretaker and yes I hate it.

A birth and a death

The business created a new entity. At the same time an old one was closed. This is important.

2 – Getting the request

On the source side, Mabel (hello, Mabel, and yes we are almost to the “I warned you, but you didn’t listen” bit) reused and renamed an existing source sheet for the new entity. This makes sense from her perspective as the formatting, formulas, etc. were already defined. She simply put in a new description, new base numbers, and the existing source worksheet did its magic. Thanks very much Microsoft.

Over on the target side, because there were so many sheets, because I do not really know the entity structure, because this is a manual process, and mainly because I am a dope, I did not follow Mabel’s lead. This was A Bad Thing as we shall see.

3 – Adding the sheet

As the layout of all of the sheets are the same I copied an existing target send sheet – note that this was not the dead entity target sheet but another one. Yes, that was another Bad Idea.

Being the super ultra-clever chap that I am (ahem), I knew that I would have to change the link formulas in the new target sheet and duly did so.

But I also did not delete the old send sheet for the closed entity. This was not a super ultra-clever act and is really the key to the error.

4 – Doubling the data

So what happened? As I showed above, Excel keeps an internal name for all of the source worksheets. A simple sheet rename doesn’t break the links. This is good, right? Right? Wrong.

Not deleting the dead sheet meant that Excel now linked twice to the renamed source sheet, once for the old dead entity and again for the new entity. As there was supposed to be no new data in the dead entity (remember the Cameron is a dope factor) I then managed to double the data in Essbase. Oops.

And this is, btw, precisely what Mabel warned me of.

Ameliorating the problem in the future

Putting aside the issue of me as a user of anything but the most basic of Excel workbooks, how can something like this be avoided?

Excel is not the answer

Excel has auditing features, but it does not (at least as far as I can see) have a simple way to show what the linked worksheets are except by examining each sheet (not terribly useful when there are 70 sheets in play) or by writing a custom VBA macro to try to report the information. Both of these are difficult-ish and time consuming. There has to be a better way.

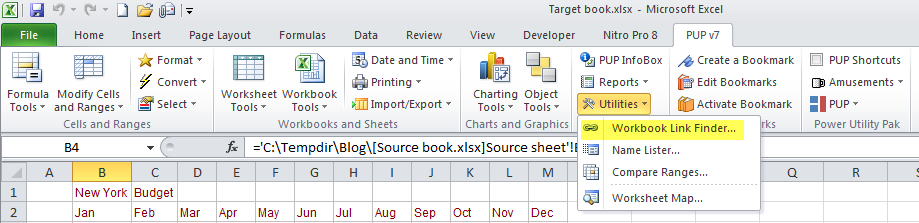

The famous John Walkenbach wrote this utility and it is, in a word, awesome.

Without going into all of the many features of this tool, and there are many, I will focus on the bit that gives you an audit report of linked worksheets.

The Workbook Link Finder is exactly what I should have used.

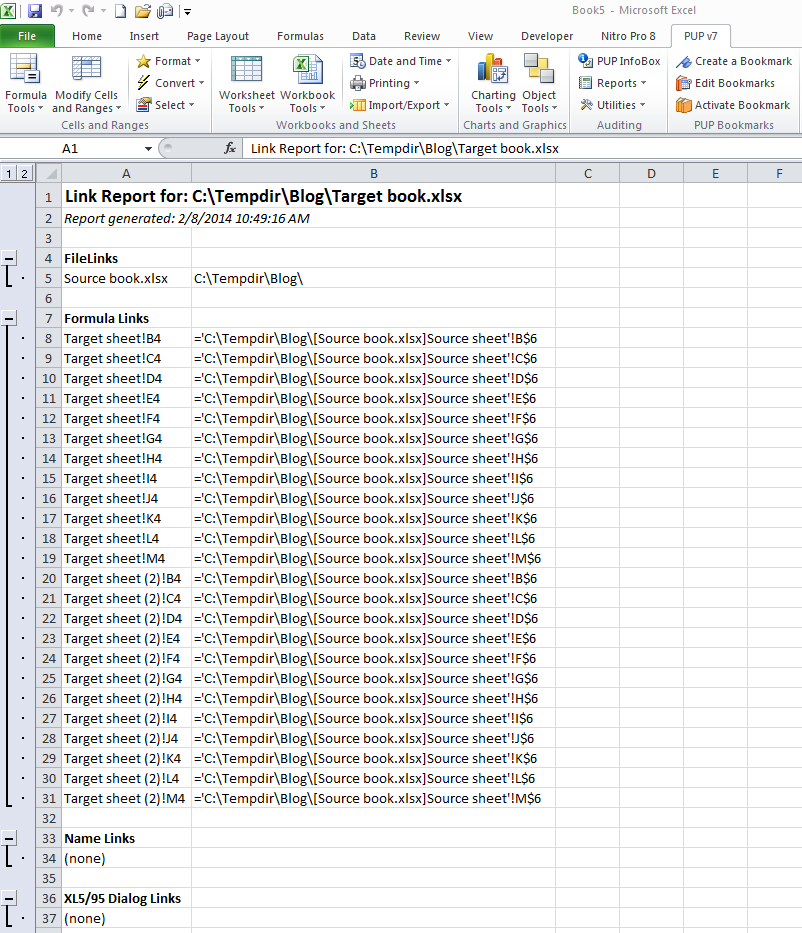

PUP even gives you a way to display the links:

Given a target workbook with a copied target sheet (just what I did in real life), the following report comes out of PUP:

Looking at the above report, I can easily see that Target sheet and Target sheet (2) both link to the same source sheet. In my example, this is precisely what I did not want to happen, but did.

Check it out for free

J-Walk has a free trial download available here. I encourage you to try it out. I am going to buy another copy and install it (if I am allowed) on my client laptop.

What have we learnt?

I think this can be summarized into a few key points:

- Cameron the Essbase hacker is not Cameron the Excel hacker.

- Yet Another Manual Process (YAMP) equals Yet Another Chance For Failure which begets Yet Another Stupid Excel Trick

- Tools like PuP can make life a little less painful

- Linked workbooks are evil

Okay, the last bit is just my opinion, but my goodness a simple Excel error led to a big Essbase data problem.

Be seeing you.